Words for a conversation in the wake of children militant

A conversation on social media between two friends I respect and admire, regarding the “March for Our Lives” protests, contained an exchange in which one of the interlocutors expressed the desire to locate the demonstrations squarely within the bailiwick of “pro-life” advocacy. Another interlocutor was not so much reticent to accept that location, as unsure how to receive it. That is a perplexity many of us are experiencing right now, and one through which it is worth working together. I hope the words of mine to follow, which draw on the words of others I respect and admire, can be words for a conversation.

If we take seriously the idea — epitomized in the words of Dr King in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail — that “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust,” we must admit that every properly basic question of how we ought to order our lives together is a “pro-life” issue. Here’s the rub: when everything is a “pro-life” issue, nothing is. Said slightly differently, the term is evacuated of its content, and left to be filled with whatever the manifesting party happens to have to heart. It isn’t that the demonstrators are wrong to think their cause a “pro-life” cause in some appreciable and even significant sense. It is that the intellectual procedure that underwrites and is supposed to undergird the asserting of “pro-life” status for the cause, actually undermines the foundation on which a sound and robust “pro-life” position may be staked.

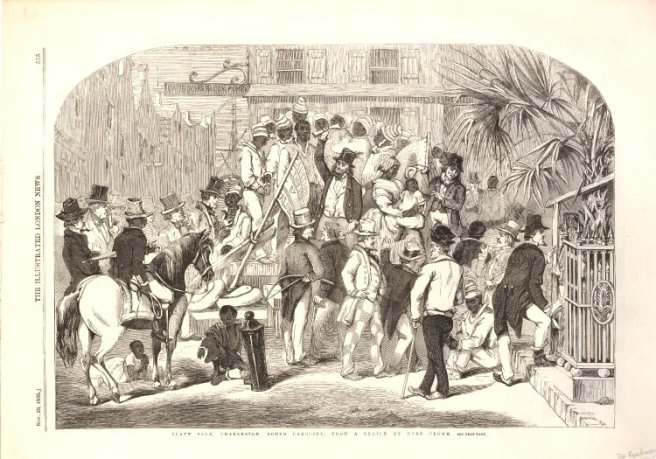

This is particularly evident when one views the issue of our epidemic gun violence problem in confrontation (in the French and Italian sense of the term) with abortion.

Procured abortion is the direct and deliberate destruction of innocent life. We can say, on purely rational and reasonable grounds, even making a prima facie case, that – to paraphrase St Teresa of Calcutta – if abortion is not wrong, nothing is. Opposition to abortion is “pro-life” in the prosaic and even pedestrian sense that one is for protecting innocent life from precisely the deliberate harm and destruction that abortion is.

To the extent the protesters want to see an end to the mass murder of schoolchildren by firearm, their position is evidently “pro-life”. The matter is complicated, however, by three considerations:

- Guns are not evil per se, nor even are gun manufacturers. Many of the uses to which we put the former are evil, as are many of the methods of the latter, especially insofar as the plying of their trade is concerned. Many of the former and the latter are not.

- There is no single “pro-life” position in opposition to the admittedly intolerable status quo, around which the marchers are demonstrating, e.g. the appalling miscarriage of justice that was the SCOTUS decision in Roe.

- There is a constitutional right — spelled out in words — to keep and bear arms. Where that right is located and what are its limits, and which are the proper constraints to the exercise of it that it is in our power to place, and which among those last are prudent at any given time and place, are all matters of urgent public import.

What we are witnessing is a groundswell of enthusiasm that has yet to find direction, scope, purpose within the national discourse. This movement has a great chance to be a powerfully effective force for good. As things stand now, however, the thing could just as easily go the other way.

That is a statement of fact, and one that responsible leaders of great movements in America have frankly acknowledged when they have been at their best. “It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro,” Dr. King argued from the rostrum on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963. “This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality,” he continued. He concluded that portion of his speech saying, “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” Those lines of his also contained the following admonition:

Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.

Today, I hear those words as a twofold warning: against an attitude of dismissiveness on the part of our elected leadership especially and the broad public more generally; against the temptation to confuse emotion with reason and to conflate the two. The emotion of our children and young people is real, and raw, and will demand a reckoning that, should we fail to give it them, heaven most surely shall not. Nevertheless, sentiment is not argument.

I must say that I am glad that my son is returning to our country to continue his education in these heady days. Our young people are truly an inspiration. They may save the republic, or destroy it. Whichever it is, they will need our help to do it. Here, another great American may be of help to us. Teddy Roosevelt once said:

I want to see you game, boys, I want to see you brave and manly, and I also want to see you gentle and tender. Be practical as well as generous in your ideals. Keep your eyes on the stars and keep your feet on the ground. Courage, hard work, self-mastery, and intelligent effort are all essential to successful life. Character, in the long run, is the decisive factor in the life of an individual and of nations alike.

Teddy was speaking to boys, and he meant “boys” when he said it, though in our day we happily see that his exhortations rightly apply in equal measure to our girls — and that there are qualities of manliness, in the sense of homo and ἄνθρωπος, which it is the particular province and task of our fellows of the female sex to demonstrate — who are recovering a sense of their especial and unique dignity and taking their place in the leadership of our society.

In any case, Teddy exhorted the boys to the practice of those disciplined excellences of character and disposition precisely because they are indispensable to the man and the citizen of a healthy republic. We must model them for our young people even as we demand of them their practice unto perfection.

When the people who became the American people were debating the great question, whether they should be a people at all, and if so, what kind of people they should aspire to be, Alexander Hamilton brought together two other leading men of the founding generation under the allonym, Publius [Valerius Publicola, hero and savior of the Roman republic], framing the question before them in these terms:

[I]t seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.

After the events of this weekend, I believe more strongly than ever that we are at a point in our national life, in which, again to borrow the words of Publius:

[T]he crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

Publius went on to remind the people of New York that:

[I]t would be disingenuous to resolve indiscriminately the opposition of any set of men (merely because their situations might subject them to suspicion) into interested or ambitious views. Candor will oblige us to admit that even such men may be actuated by upright intentions; and it cannot be doubted that much of the opposition which has made its appearance, or may hereafter make its appearance, will spring from sources, blameless at least, if not respectable–the honest errors of minds led astray by preconceived jealousies and fears. So numerous indeed and so powerful are the causes which serve to give a false bias to the judgment, that we, upon many occasions, see wise and good men on the wrong as well as on the right side of questions of the first magnitude to society. This circumstance, if duly attended to, would furnish a lesson of moderation to those who are ever so much persuaded of their being in the right in any controversy. And a further reason for caution, in this respect, might be drawn from the reflection that we are not always sure that those who advocate the truth are influenced by purer principles than their antagonists. Ambition, avarice, personal animosity, party opposition, and many other motives not more laudable than these, are apt to operate as well upon those who support as those who oppose the right side of a question.

Let us remember that we are citizens of a great republic, with a duty to face our failures squarely and without stint, and an equal one not only to preserve but to foster and allow ourselves to be guided by the best angels of our nature, knowing that we will often be preserving them against what is worst in ourselves. Let us all give those better angels some exercise now.